Clay Quarterman

A Short History of EPCU

Breath of God in the Borderlands

Uninformed people think that Protestants are a novelty in Ukraine. Although recent heretical cults do exist, Reformed churches represent historical Christianity, and have a long history in Ukraine.

Reformed congregations existed in Odessa from its founding, and many Reformed Churches existed across Ukraine – even as far back as the 16th century. But these congregations were mostly eliminated by the purges of atheistic Communism.

At the end of the 20th Century, however, those roots were revived from western branches of the Church, when many churches sent workers to fill the void left by the atheism of the USSR. Among others, the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) sent missionary teams to live in southern Ukraine, and the Spirit of God raised up churches and leaders through the preaching of His Word. These churches formed a national denomination -- the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Ukraine (EPCU) – spreading the light of the Gospel across Ukraine and beyond.

Why another church in Ukraine?

Ukraine had just celebrated 1000 years as a Christian country when missionaries arrived from the west in 1993, and Odessa was about to celebrate its 200th anniversary. Was it presumptuous for these foreigners to plant new churches here? Was this a “foreign invasion” of a “foreign religion”?

No, this was the revitalization of the Reformed faith in Ukraine. Ukraine’s Reformed Christian heritage stretches back to the 16th century Reformation, when Reformed churches sprang up in territories that are now part of Ukraine. These Reformed roots had been renewed in the 1920s and again in the 1990s.

These western Presbyterians’ goal was not to establish a franchise of their organization. Their goal was to help spread the Gospel in the former Soviet Union, where the Gospel itself had been persecuted and had not been widely preached or understood for generations.

Ancient Religion

What is this Gospel? It is not merely Christian symbols and traditions, but the reality of a community living in covenant relationship with the Triune God, according to His Word, the Bible.

The Presbyterian Church is considered a Reformed church, since it was established in the year 1560 as part of the Protestant Reformation, “protesting” against moral and doctrinal errors and “reforming” the church according to the teaching of the Bible. They sought a return to the ancient Christian faith.

This Presbyterian Church is first and foremost a Christian church, holding to the creeds of historic Christianity. It uses the Nicene Creed, the Ten Commandments, and the Lord’s Prayer in its liturgy. It holds to the Holy Trinity and the historic Creeds, not simply out of tradition, but because these are the teachings of their final authority, the Bible.

Biblical Religion

All historians agree that by the 16th century the western church had become very corrupt. People longed for morality and truth, rather than the despotism of corrupt priests. The Reformation movement arose, saying Truth can be discovered by looking carefully at the Bible.

At that time, the Renaissance was calling men to return to ancient texts, and the German scholar Martin Luther did so. He rediscovered in the Bible this simple truth: “The Just shall live by faith” (Rom. 1:17). He realized that Christianity had been twisted. Instead of living by faith, religion was made into something Man must DO on his own in order to earn favor with Deity – whether by good deeds, pilgrimages, donations, prayers, abstinence, rites, or candles.

But the simple truth of this rediscovered Gospel was that God is merciful, offering salvation through faith in the finished work of Jesus Christ. The Reformers taught that the way to morality was simply to receive and trust upon Jesus’s work, rather than trying to accomplish salvation by our own works. The Reformers discovered that this is nothing new, but the ancient teaching of the Bible itself, as taught by the Apostles, St. Augustine, and the other Church Fathers.

Martin Luther began publishing this in 1517; he wanted simply to correct and purify the church. The established churches rejected the Reformers, however, so Luther, John Calvin, and others had to re-form the church – reforming all its beliefs and actions by this one standard: “according to the Word of God” (Sola Scriptura, in Latin). Such Reformed Churches were founded across Europe -- in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, France (until 1572), England, Hungary, … -- and even in Brazil!

The Presbyterian Church was one of these churches, founded in Scotland in the year 1560, when John Knox, a student of John Calvin, applied these teachings to his own nation. This Presbyterian model was later carried to America by its first settlers, forming the basis for the Pilgrims’ life and government.

The Reformation movement became mixed with nationalistic and political motifs that changed the face of Europe, but the Reformation cannot be explained simply by politics or economics. The heart of this reform was in taking the Bible itself seriously: Sola Scriptura, applied to all of life, religion, and doctrine.

In England, Henry VIII was motivated by personal as well as religious reasons to break with Rome, but he did not fully reform the church. His daughter Queen Elizabeth I also established only a “half-way reform.”

In 1643, however, Parliament desired a fuller reform of church and society according to the Bible itself, so they summoned theologians from Scotland and England to produce the Westminster Confession of Faith and Catechisms. For over 370 years, these have been used as clear statements of faith for Presbyterians throughout the world, including the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Ukraine (EPCU).

But, when did this come to Ukraine? It came in several waves of influence.

The First Wave of Reformed Influence

Although the Eastern Christian churches were separated from the Western churches in the Great Schism of 1054, this distance did not completely separate them from reforming influences that came into the Western church – even those prior to the Reformation.

In the 15th century, followers of Jan Hus in Bohemia attempted reform, but were suppressed. But when the Hussite general Jan Žižka died in 1424, some of the Hussites fled to Ukraine: “The Hussite movement had an impact on Ukraine: among J. Žižka's forces there were supposed to be Ukrainians, and after their defeat some Hussites settled in Ukraine.”[1]

In the 16th Century, more Reformation influences came eastward. At the time, little distinction was made between Calvinists and Lutherans, with all reformers being called followers of Luther or “Lutherans”. This was also true in Ukraine. “Lutheranism has been known in Ukraine since the mid-16th century in Volhynia, Galicia, Kiev, Podillia and Pobuzhzha. Certain members of the gentry (the Radzyvil family) were Lutherans.”[2]

John Calvin even corresponded with the Patriarch in Constantinople, urging reform of the Church. During this period, “Luther’s and later Calvin’s ideas gradually reach Ukraine and Byelorussia via Poland and Lithuania. From 1520 a ban is imposed on bringing Protestant literature into the Polish kingdom.”[3] Nonetheless, in “1562 – Simon Budny is the first to publish the Calvinist Catechism and the work ‘On the Justification of Sinful Man before God’ in Cyrillic.”[4]

And when the Uniate project was attempted at Brest in 1596, many Protestant advisors were also present, for in this period “Approximately 100 Protestant congregations exist in Ukrainian lands under Poland”.[5]

The Reformers’ goal, though, was not to “invade” or establish a new church organization, but to reform all churches that name the name of Christ. Serhii Plokhy, professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard, wrote in The Gates of Europe that he considers the Brest agreement as part of the Reformation, with both western and eastern parties being reformed in the process. This purification was precisely the Reformers’ intent.

Reformed writings convinced Patriarch Cyril I Lucaris to write a Reformed Confession[6] in 1629 for use in the churches of the East, but political influences were brought against him, and he was murdered in 1638. Surprisingly, although this work was later condemned, he was highly honored in the church, and he was even recently canonized in the year 2009.

The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies published an article on the “Reformation” which details more of this influence of the Reformation in Ukraine:

“Reformational ideas were introduced into Ukraine by students returning from their studies in Bohemia and Germany and by Hussite and German colonists in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. By the 16th century the ideas had become popular among many noble families …in the Commonwealth. After the 1569 Union of Lublin reformational congregations were established in Ukraine (63 in Rus’ voivodeship and Belz voivodeship, 27 in Volhynia, 6 in Podilia, and 7 in the Kyiv region and Bratslav region).”

“The Reformation had a marked influence on Ukrainian religious-cultural life. Czech Protestant translations of the Bible were already being used in Ukraine in the 15th century, and in the late 16th century, Ruthenian translations…. Thus, under the influence of the Reformation a bookish Ruthenian language gained currency….”

“A number of reformational schools were founded in Ukraine, including Calvinist ones in Panivtsi, in Podilia, and Ostrih and Berestechko, in Volhynia, and Socinian schools in Kyselyn, Hoshcha, Cherniakhiv, and Liubar, in Volhynia. Their quality of education often surpassed that of the Catholic schools, and they attracted many Ukrainian and Belarusian students.”[7]

The reformational influences remained, but the movement did not. “The influence and successes of the Reformation did not endure in Ukraine, however. Its link to Protestantism placed it between two warring camps, Catholic Poland and Orthodox Ukraine, both of which grew increasingly antagonistic not only to each other but also to reformational currents.”[8]

Eventually, “the Orthodox church became hostile to Protestants in general” and “the Ukrainian uprising of the mid-17th century under Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky …opened the way for the penetration of other cultural and political currents…. Most of the reformational communities in Ukraine ceased to exist around that time.”[9]

“Mylkhailo Drahomanov spoke longingly of the Reformation. For him, the whole of Ukrainian history was a history interrupted (‘cut short’), while the history of Ukrainian Reformation was a history of the Reformation interrupted.[10] Ukraine could have grown with Europe if our Reformation had not failed. But, instead of the Reformation, there is a yawning gap in Ukrainian history of ‘rupture and ruin.’”[11]

Second Wave of Reformation in Ukraine

Russian and Ukrainian Baptists speak of a “Second Wave” of the Reformation in the 19th century in Russia and Ukraine,[12] tracing their own origins to Lord Radstock in St. Petersburg and to the Stundists in southern Ukraine. Yet, Reformed believers preceded this wave.

The Stundists trace their beginnings to 1858 in Bible study groups, but it was a Presbyterian, John Melville, who preceded them, beginning evangelism and Bible distribution in Odessa oblast in the year 1823. The complete Bible was not fully available in the Ukrainian language until a translation was published by the British Bible Society in 1903. This Bible only became available in Ukraine after the 1905 Revolution, when Czar Nicholas II issued a manifesto of religious toleration. The pietistic Stundist movement and others then spread, leading to the founding of national denominations with close ties to the Protestant west.

Yet, even in the two centuries prior to this, some of the western immigrants were Reformed, establishing their own immigrant churches, such as those in Kherson and Odessa.[13] This previous influx of Reformed Protestants can be considered much more of a Second Wave of the Reformation in Ukraine. How did this come about?

Toleration under Peter and Catherine

The Reformation was mostly resisted in Russia and Ukraine in the 16th and 17th centuries, but a period of greater toleration came under Peter the Great. Having personally observed the influence of the Reformation in the Netherlands, Peter opened doors of religious toleration to Western religions. He decreed in 1705 that Protestant churches could be established in the empire, and by 1708 a Lutheran church was established in St. Petersburg.

Then, when Empress Catherine settled southern Ukraine in the latter 18th century, she invited settlers from the West, who brought their religion with them. Many Lutherans and Reformed emigrated together, often forming joint communions.

The village of Shabo (Odesa oblast, near Belgorod-Dnestrovsky), was founded in 1822 by Reformed settlers from Vevey, Switzerland. Shabo is famous for its wines, and the Vineyard Museum tells the immigrants’ story, displaying a rifle and French Bible from that time. Each family had its own Bible, and the Reformed church building still stands in the village.

It is rather ironic that in the 1990s, when a Reformed Presbyterian church was established in nearby Belgorod-Dnestrovsky (along with a Christian Clinic and other ministries), its pastor, Sergei Betin, came from Shabo.

Musket and French Bible in Shabo Museum

Odessa Reformed Congregation

The Reformed believers in the city of Odessa arrived even earlier. Odessa was founded by Catherine in 1794, drawing architects and entrepreneurs from the West. Catherine allowed them to establish their own churches there. The Lutherans and Reformed worshiped many years in a joint congregation in Odessa, sharing a common pastor. Bienemann writes in his History of the Evangelical Lutherans in Odessa:

“The Odessa Protestant congregation sought its pastors from the University College of Theology in Dorpat, Estonia. The first Protestant pastor to be appointed to Odessa was Johann Heinrich Pfersdorff. … When the pastor’s house in the village of Großliebenthal was completed in 1806, he relocated there…. In 1811, …a pastor was specifically appointed to the city of Odessa…. The new pastor for the city of Odessa was Carl August Böttiger. At that time, the Odessa congregation still worshipped in a rented house, as they had no church.” [14]

Various other pastors are mentioned of this joint Protestant parish: Johann Ambrosius Rosenstrauch and Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Fletnitzer, who stayed for forty years. In 1825, they started a church school. In 1827, the original church of St. Paul’s was dedicated in Odessa.

However, the Empire established a new set of laws in the 1830s, making the joint relationship difficult. “Until then, the Lutheran and Reformed denominations in Odessa had worshipped together in the same church, but because of the new Church laws, the Odessa church became known as the Evangelical-Lutheran church. That move was to result in the Reformed Church members breaking away and forming their own separate congregation in 1843.”[15]

These were both clearly foreign churches, and they remained foreign by Czarist authority. Yet, this foreign and cosmopolitan nature was endemic to the whole city being founded by Catherine. Odessa was a city made of many nationalities, for which the city is still famous.

A legal brief researched for the Odessa court in 1988 shows the international flavor of Odessa’s Reformed church in its early years: “Austrians, Englishmen, Germans, Frenchmen and Swiss attended the meetings. Preaching was alternately in German and French. The communion was led at different times by pastors I. F. Lobschtein, G. Henry, K. A. Candidus, I. Kleingass, and others. … In 1914: permanent pastor was Eugene Ivanovich Kornman”.[16]

The Reformed congregation developed its own unique presence in the city, comprising some of the city’s first citizens and most influential builders:

“The Evangelical Reformed Church of Odessa existed in the first years of the construction of the city…. In 1837, the Richelieu Lyceum, located until then in the Wagner house on Deribasovskaya #16, received a new building. In the courtyard of Wagner home was located an orthodox chapel for the lyceum, named after the saintly prince Alexander Nevsky. After the lyceum moved, they began building a new chapel. But the old temple was given in that year to the Evangelical-Reformed Communion of Odessa, which by 1842 remodeled it according to their own regulations. On 20 March, 1894, a new church building of this communion was proposed on Khersonskaya Street #62 under an architectural project of A. Bernadazzi and V. Shretera.”[17] This is the church that still stands on what was later renamed Pastera Street.

Pastera Reformed building in 1905

The Lutherans also built their own building, the Kirche in Odessa. Both buildings were eventually confiscated by the communists and misused, allowing them to fall into disrepair. “In Soviet times, the church was closed and under a plan of A. Minkus, was transformed into a puppet theater.”[18]

In the 1990s, however, both buildings were returned to their religious communities. The Lutherans and Presbyterians restored these buildings, which are in active use today as houses of Christian worship.

Reformed Churches under Communism

In Soviet times, the atheists tried to eradicate Christianity, but they were not fully successful. People continued to observe Easter, along with their traditional Christian greetings. Grandmothers secretly had their grandchildren baptized. Many believers went underground.

Communism was a new type of “religion” intended to replace the old -- uniting church and state, placing all worship, churches, and beliefs under the State’s authority. Their initial focus was to annihilate the political power of the State church (the Orthodox church), which was closely allied with the Czar. Among notable events in 1937, “By a decision of the Soviet government all Orthodox churches under various jurisdictions are officially liquidated in Ukraine. The Soviet government orders the dismantling and destruction of 2900 churches and 63 monasteries in the U.S.S.R. The Scottish Bible Society publishes a report on the destruction, closures, and the conversion to other uses of 70,000 churches in the Soviet Union by the year 1937.” By January 1939, “Not a single Orthodox bishop remains on the entire territory of Ukraine.”[19]

Initially, however, the Soviets allowed Protestant churches an unprecedented time of freedom. When Transcarpathia became part of Czechoslovakia at the end of WWI, the Reformed Church in Transcarpathia was founded (in 1921) with 77 congregations of ethnic Hungarians.

During the 1920s, even while thousands of Orthodox churches were being razed to the ground, missionaries came from the west, rapidly planting new Reformed churches. By 1925, ninety churches had been started in western Ukraine, and the Ukrainian Evangelical-Reformed Church (UERC) was founded.

Choir of UERC in Stepan, 1925

By 1939, this church had “35 church communities, 15 preachers and approximately 5,000 members.”[20] The UERC celebrated its 80th Jubilee in Rovno on Reformation Day 2005, which was also attended by Odessa Presbyterians.

The communist persecution was soon expanded, however, and all churches were subjugated, infiltrated, or driven underground in the 1930s. Among Baptists, for example, it is recorded that by 1939 “all pastors and missionaries are shot, exiled or imprisoned.”[21] By 1939, the Reformed churches were all but annihilated.

"According to Soviet data, on the territories of Ukraine which became part of the U.S.S.R., 6,371 churches (out of 14,371 in 1914) were destroyed or changed into structures for other uses (jails, schools, clubs, warehouses) during the period 1917-1932... All church communities in Ukraine... were liquidated by 1937."[22]

Yet, a few leaders remained. Reformed Pastor Philemon Semenyuk, ordained as a Reformed pastor in Kolomia in 1925, suffered prison for the faith, but survived to see Reformed churches revived in the 1990s in Rovno, Stepan, and Svalyava.

A Third Wave of Reformation

As Ukraine emerged from Communism in the 1990s, in spite of having the vestiges of Christian ceremonies and buildings, most people were atheists and had little or no understanding of the Gospel itself. What is the Gospel? And where would they hear it? Some of the churches in Ukraine had been driven underground; others were controlled or even compromised. Many evangelical churches had become anti-intellectual, since identification as a Christian cut off one’s opportunities for higher education. Once freedom came, many churches continued in a protectionist or “fortress mentality”. Some churches were mere cultural enclaves rather than living churches, and there was little zeal to reach the surrounding culture.

With the failure of ‘Perestroika’ and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, there came not only freedom, but also the societal dysfunction of the 1990s. People were looking for answers that only the Gospel could bring… and they largely weren’t hearing it.

Suddenly, after 70 years of being closed off to the influence of western churches, the doors of the former USSR were flung open for Gospel ministry. Missionaries began coming in from the west, but most did not come to attack the churches that were here. Instead, they felt an urgency in this new time of freedom to proclaim the one, eternal Gospel to people in need.

These missionaries had been praying for decades for those behind the “Iron Curtain.” They had supported those who were smuggling Bibles across its borders, for the Word of God has no boundaries. In fact, Jos and Marlies Colijn and Martin Nap (who became co-founder of ERSU Seminary) were among those bringing those Bibles, until God opened the doors to them for more direct ministry.

CoMission: Evangelism in an Atheistic State (1993-5)

God opened the doors to these western Christians in a marvelous way. Seeing the opportunity, members of Campus Crusade for Christ were granted an audience with Olga Litsenko, the Assistant Minister of Education of the (former) USSR on 5 November 1992. They proposed to send educators into the public schools to teach Christian Morals and Ethics, and they were shocked to be invited to do so! A coalition of 70 churches and mission agencies was formed in the USA to meet this huge challenge, calling it “CoMission”.

Olga Litsenko, Asst. Min. of Education of USSR, with the author in 1993

One of the most active agencies was Mission to the World (MTW), the mission arm of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Each agency took responsibility to reach a section of the former USSR, and MTW was providentially assigned to southern Ukraine, beginning in Odessa.

MTW appointed Jim Young to head up their CoMission effort, and they recruited Tom Courtney (in Spain), Hugh Wessel (in France), and Clay Quarterman (in Portugal) to oversee the teams. Horace & Mary Jane Sanders of Birmingham, Alabama, spent several weeks in Odessa, setting up apartments for the new teams. In June 1993, Quarterman and Young interviewed interpreters at Odessa State University (Mechnikov).

MTW was committed to church-based mission; the goal was not just evangelism, but church planting. They not only recruited one-year workers for CoMission, but long-term church planters to follow up on the project. Dave Smith, Dal Stanton, and Clay Quarterman were recruited as a church-planting team, and each one visited Odessa in early 1993. They met in May 1993 at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, to plan their future ministry. In August, Clay accompanied the PCA’s first CoMission teams at their training in Illinois. These first two CoMission teams left for Odessa on August 18, 1993, and began their year-long work in the public schools.

In November 1993 CoMission sponsored a “Convocation” event with 300 school teachers, meeting at Odessa’s Military Officers Club (Dom Ofitserov, #7 Perehovska). A contingent of some twenty PCA pastors came from the USA, including members of the MTW Committee: John Kyle (Coordinator of MTW), Don Patterson, Dominic Aquila, Bill Barton, Shelton Sanford, Charles McGowan, Neil and Nancy Gilmore, Gerald Morgan, Jim Young, etc. Clay Quarterman came, but his luggage did not, and he had to borrow clothing from his colleagues. The ministry of education greeted them with traditional Ukrainian dancers and bread and salt. This traditional greetings was in shocking contrast to the previous half century of Cold War between their counties. “Druzhba” was the spirit of the times, but this friendship became a lasting reality in the churches that were eventually planted.

These Ukrainian educators opened the doors for CoMission’s work in the public schools of Odessa. From 1994-1997 MTW sent 12 CoMission teams to the southern Ukrainian cities of Odessa, Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, Izmail, Nikolaev and Kherson – over 100 American volunteers who came at their expense to live in Ukraine for a full year. The teams showed the “Jesus film” and gave out Bibles and literature, built relationships, shared their testimony of personal relationship with Christ, and formed several local Bible studies for adults. However, this project was approached as an educational project, and church planting was left up to the church planting teams.

The First Churches of the EPCU

In May of 1994, the Stanton, Quarterman, and Smith families met at the Twin Lakes retreat center in Mississippi, working out much of the philosophy and strategy for the Odessa Church Planting Team. Dave Smith was appointed team leader and produced comprehensive guidelines that would focus their work for a decade. After studying Russian for 4 months, the Quarterman family moved to Odessa in July 1994 and established a humanitarian aid organization (Renewal Enterprises/Sodeistviye), through which also the other team members could be invited into Ukraine.

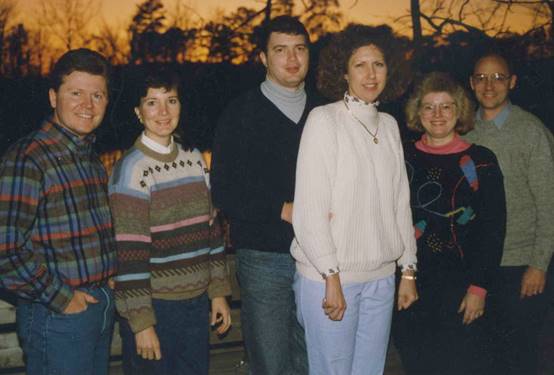

Dal and Beth Stanton, Dave and Dee Smith, Clay and Darlene Quarterman

The Quartermans took over the seven weekly Bible study groups of CoMission in July and August, until the second CoMission teams could arrive.

Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, 1994

In Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, an additional CoMission team was half way through their first year when the Quartermans arrived, and God was raising up leaders fast. On July 30, 1994, several CoMission members and Clay Quarterman met with visiting PCA pastor Paul Alexander (of Huntsville, AL) to examine 26-year-old Ivan Bespalov as a prospective student for seminary. Bespalov was later trained and became one of the first ordained pastors of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in Ukraine (EPCU).

CoMission Team in Belgorod 1994: Fred and Emma Peace, Joey & Fran Parsons, Cindy Manning, Chris Starnes, Amanda Champion, and Kevin Ellis

As the Belgorod group developed, they chose a name in January 1995: Ïðåñâèòåðèàíñêàÿ ãðóïïà ìîëîäûõ õðèñòèàí (Presbyterian Group of Young Christians), wanting the name to be palatable to non-Christians and Orthodox. By February 1995, they were already talking about baptisms and how to organize the church for worship and membership.

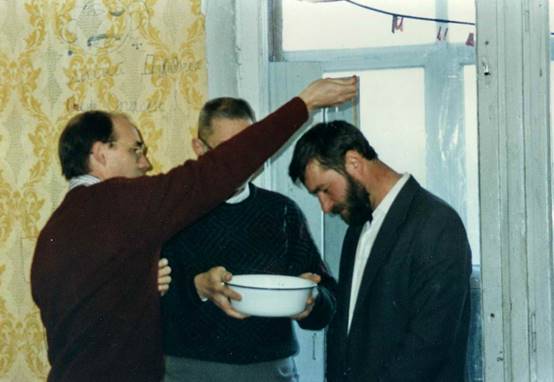

Victor Lukoshkin; the first Presbyterian baptism in Ukraine after the fall of the USSR

Alex & Renona Munro of New Zealand, former missionaries of the Christian Reformed Church to the Philippines, joined the MTW Church Planting Team for a year. They were assigned to Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, and by the time they left, the group had clearly changed from a Bible study group to a local church. This became the first Presbyterian church to be organized in what would become the EPCU.

After meeting in homes, then a museum, this group met for years in the club for the deaf. They then established a Christian clinic and met there for worship. But they then purchased a large building in the Pobeda district, which was dedicated on June 27, 2008. Dr. Larry Roff brought a choir from the USA. In December of that year, he dedicated a pipe organ he had arranged for them – a novelty and cultural coup in this town of 50,000 people. A visiting choir also came from the historic Tenth Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and a number of foreign organists have given concerts of religious music in the church.

On June 7, 2009, three elders were ordained, and the church was organized as a particular congregation of the EPCU, with Rev. Sergei Betin as pastor.

Odessa Easter Fellowship, 1995

As the missionaries and educators of CoMission worked in Odessa, new people came into a relationship with Jesus Christ, and these people needed to find a church home. Most were neither Orthodox, Baptist, nor Pentecostal – they had been atheists. Yet, they had come to love the Bible and its teaching and the prayer and fellowship of their small groups. Although some of these joined existing churches, many did not feel at home there – some churches were too traditional, others too modern; some were cold and taught little, allowing little participation. Where could these people find the same powerful message of the Reformation? It was decided to invite these people to join together for fellowship at Easter.

This first religious fellowship meeting was held on Saturday, April 15, 1995, with songs, testimonies, discussion groups, and a drama team. Members of the various CoMission Bible studies were invited, and Keith Ward played guitar. This pre-Easter meeting was held in the 3rd floor meeting hall of the Oblast Dental Polyclinic at 27 Torgova St. (Krasnoi Gvardi 15) , near New Market. Ivan and Lucy Bespalov and Sergei Betin shared their personal testimonies, among others.

It was decided to meet there again the following month, but when the worker with the key failed to appear, it was decided to meet in the park nearby at Primorsky Boulevard, on a grassy knoll overlooking the bay. This became our meeting place for the summer, sitting on the grass in the open air.

Odessa Presbyterian Church

During the summer of 1995, PCA Ruling Elder Ed Robeson of the CoMission team helped Clay Quarterman in organizing the worship services in the Park. Sergei Betin of Belgorod-Dnestrovsky was the “emcee” (Master of Ceremonies), and Ivan Bespalov was learning to share the Scriptures. It was decided to hold worship meetings once a month.

When colder weather came, they met in a rented gymnasium in the school at Pushkinska 28, and meetings became more frequent. The first baptisms and communion were held there, under the basketball goal, on Easter 1996. Conditions were not optimal there, sitting on tiny gym benches, so worship was moved to the Medical Workers Club at Grecheska 20, where they remained a lengthy time. For a short period they met in the Lesi Ukrainki Culture Hall at 38 Bunina St. All this peregrination made them seem like a cult, yet, their identity and unity were secure in their relationship with Christ as they enjoyed the historic Christian teaching and biblical preaching.

But God had a big surprise in store!

Odessa Church building

The Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Odessa (EPCO) was registered on May 21, 1996. Shortly thereafter, it was discovered that the so-called “Puppet Theater,” a well-known building in downtown Odessa, had originally been built as a Reformed church! It was constructed precisely 100 years previous by French and German settlers from Alsace-Lorraine, before it was confiscated by the Communists.

Most of the building was not in use, and a presidential decree was invoked in court for the return of this stolen property. The court agreed, naming the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Odessa the “sole moral and legal heirs” to the property on Thanksgiving Day, 1998! This building and the court decision give the Evangelical Reformed Presbyterian Church of Odessa a direct connection to the original congregation, and this gives them a clear claim to two centuries of history in Ukraine.

It was during worship at Grecheska that the congregation received the keys to the building, and they made an impromptu religious procession from there to Pastera 62, being able for the first time to view the interior of the building that would be their future home – right on the corner of Pastera (Khersonskaya) and Preobrazhenskaya (Soviet Army St.), facing Odessa City Park (Gorsad).

The American church (PCA) committed to repair the derelict building, a beautiful structure on the national register (designed by V. A. Shreter, who also designed the Kiev Opera House and notable buildings in St. Petersburg). Quarterman headed MTW’s largest capital funds project, and over $1 Million USD was raised. Reconstruction began in June, 1999.

An Actors’ Guild had been allowed to meet in the first floor of the building until that time, and protested the church’s claim, in spite of the church paying them a large indemnification. This contest continued in the courts for 9 years, only being resolved by the Supreme Court of Ukraine in 2009. During this time, the church proceeded with the restoration project on the other areas of the church.

When the Communists took the building, their sacrilege extended to sawing the cross off the steeple, and it was found 70 years later, still lying there on the roof. It was a joyous and much-awaited moment when a cross was reinstalled on the steeple on June 7, 2003, indicating the building’s return to its original purpose.

A building dedication ceremony was held on July 22, 2001, attended by 400 people, 40 international visitors, and the Kiev Choir and Orchestra of MMK. Local TV and news media were present to capture the story, and a professional video was made of this special event: "Celebrate the Glory." The history of the building was also told in the award-winning video "Restore the Glory" (1999), as well as being broadcast in the public media in Odessa.

Odessa Sanctuary, fully restored

The Odessa church elected its own pastor and elders, and they were installed in a special service on December 9, 2001, when the church became a self-standing church and a full member of the EPCU.

Odessa Pipe Organ:

When PCA pastor Larry Roff visited the Odessa building, he felt the sanctuary “had” to have a pipe organ. Dr. Roff raised funds over six years, and a 5-rank pipe organ was purchased with 75 additional digital ranks. This Walker organ was featured at the General Assembly of the PCA in July 2003, then shipped to Ukraine and installed in July 2004. Pastor Roff played a dedicatory concert, and the event was featured in all the local media. It has been very effective in accompanying worship, in outreach, and in service to the community, even drawing international organists from France, Poland, and the USA. Free concerts are given there monthly by local and international musicians. It is one of the best pipe organs in Ukraine, and it is perfectly adapted to its setting.

Young Adult Ministry

In the fall of 1995, Doug Shepherd began a ministry that became the foundation for an active Young Adult Ministry (YAM) in the churches. It quickly became evident that an American University ministry model would not work in Ukrainian culture. Therefore, relationships with young people aged 18-30 were deepened and networks were begun, as opposed to setting up a campus group. This “new generation" of young people proved to be very open. The group began with six students and grew to 35 by the fall of 1996, meeting in Doug’s apartment. As the group grew they moved to a gym were they averaged 45 in attendance. By the year 2000 there were over 40 young adults and members of the Odessa church active in YAM. In 1997 Doug began to train the first Ukrainian YAM leader: Masha Nagribetskaya. She took over as National YAM Director in the fall and became a part of the missionary team. Masha also eventually became Doug’s wife. Doug was ordained after studying at Covenant Seminary in St. Louis, and they returned to Ukraine in 2006 as church planters to Lviv, developing an active ministry to university students there.

The EPCU churches have local university ministries and cooperate with other evangelical organizations such as Intervarsity (CCX) and Campus. The churches have also organized nationwide conferences for youth every spring, and they hold a nationwide conference for leadership development every fall.

Persecution and God’s Jiu-Jitsu

In spite of these successes, a challenge came in June 1997. The Odessa Oblast Committee for Religious Affairs called in the leaders of the Odessa church. They told the leaders that Americans should not be preaching since their visas were for business and not religion. Of course, Ukrainian laws at the time were still based on Soviet laws, only granting visas to religious organizations previously tolerated by the USSR. They threatened to bring in the police, close the church, and deport the Americans if they didn't abide by this decision.

This brought an immediate crisis. Although the Ukrainian leaders in each city were being trained in theology and practice, and were already sharing the decision-making, preaching, and leading tasks with the missionaries, some were holding back until this crisis event called them forward. A decision was taken to speed up their ordination process, which was already underway. Elders Dal Stanton, Fred Peace, Clay Quarterman, and Dave Smith met on July 11 and 12, 1997, and after examination, ordained Ivan Bespalov, George Kadyan, Sergei Betin, and licensed Yuri Saklakov to preach. On October 12, 1997, Alexander Korsakov and Valera Babuinin were also ordained. (Korsakov later left the ministry and became a ruling elder in Odessa for many years.)

In the end, we rejoiced that our sovereign God had used this crisis to push leadership forward. We later came to call this “God’s Jiu-jitsu,” where something intended for evil was used for good.

Odessa

Examinations, July 11, 1997: Smith, Josiah

Bancroft (visiting PCA elder), Betin, Saklakov, Peace, Quarterman

Spreading the Good News

Work was begun in other cities in Odessa and Kherson oblasts, where schools were also inviting teachers of Christian morality and ethics. So, CoMission teams were sent there, too, usually coupled with missionary church planters. What follows is a brief register of this development in each of those cities.

Nikolaev

Nikolaev’s first CoMission team began work in 1996. By fall of 1997, they had started several weekly Bible studies as well as a weekly worship service. In November, 1997, the Nikolaev Evangelical Presbyterian Church accepted its first six members. The CoMission team left and the MTW team continued the Bible studies and organized a Sunday morning worship service, which had an average attendance of eighteen people. This grew to include forty members, with over sixty people in attendance at worship services.

Nikolaev CoMission Team: Shannon Meade, Donna Curts,

Stella Vidlak Ron and Susie Shepherd, Chris Starnes. and friends

The Nikolaev church was first pastored by missionary Heero Hacquebord, and was then served by seminary student Yuri Finko. Alexei Rayu was ordained in November 2005 as pastor of the Nikolaev church, but after a several years of service, grieved us all when he demitted the ministry in June 2009. He even left the faith, which was widely lamented throughout the churches. Since then, the church has been served by visiting pastors and ruling elder Andrei Vakulenko.

Andrei and Anya Vakulenko

Ministries of the church have included a prayer ministry, men’s and women's discipleship, Bible study groups, a young adult ministry, a diaconal ministry, and work with orphans. Two men were sent to study in seminary, serving among the church's leaders while preparing for the pastorate.

Service of Organization as a Particular Church, 2004

In 2015, the Nikolaev church was able to purchase a building which they have refurbished with their own hands, and in 2017 they were actively involved in the “Reformation500” sesquicentennial events in the city.

Cherkassy

In 2004, the Nikolaev church sent out two families as missionaries. The Presbytery ordained Sasha Bukovetsky in Nikolaev church on October 10, and dedicated the families of Viktor Ovsyanik and Bukovetsky as missionaries to move to Cherkassy to start a new Presbyterian church there.

Soon after beginning the work, Bukovetsky felt called to work in Christian publishing, organizing Colloquium Publishing. He also organized conferences and worked with ERSU seminary, developing the Bible college program which ran from 2006 to 2009. After several years, he moved to the USA and continued to work in Christian publishing.

Victor Ovsyanik was ordained as the organizing pastor of the Cherkassy Reformed Church on April 22, 2007. Victor has been a "bi-vocational" pastor throughout his years of service there. The Ovsyaniks continued the church work out of their home, where worship services were held for more than 10 years. In July 2016, the church purchased an apartment, and the first service was held there in July 2017.

The church regularly held Bible studies and a Christian film club. For several years the members of the church helped plan and carry out summer camps for children in the Cherkassy region. They also formed a church library which is actively used not only by members of the church, but also by Christians from other churches of the city.

Izmail

A Comission team moved to Izmail in 1996. Through work in the schools and university, a group was gathered and Sunday meetings were begun. Dal Stanton, Ivan Bespalov, and others traveled regularly from Odessa to hold worship services there and to train leaders. Others regularly supporting the work for years included Jim and Mary Lower, Paul Alexander, and Art and Sharon Scott.

Joey and Fran Parsons arrived in 1997 and, along with Louisa McCullough, moved to Izmail to assist the work of Church Planting. The Parsons later returned to the USA to study for the ministry at Covenant Seminary. Regular visits were made by the church planting team in Odessa until the church could be established on its own, with Pastor Andrei Getz. They purchased a building in the center of town which was outfitted for worship and classes, and the ministry there has continued.

Izmail CoMission Team, 1996: Jane Smith, Bob Burnham, Brian Gueltig, Jim & Mary Lower, Andrea Johnson (later married Bob Burnham), Justina Henry, Charlotte Hooper

Not pictured: Susan Morgan, Jeff Rogers, Danah Martin

In 2010 there was division in the church, and a group separated to form an additional Presbyterian church plant in the city, under oversight of the Belgorod church. But the groups were reunited in 2017.

Ordination of Pastor Andrei Getz, Izmail, 2006

Kiev Holy Trinity Church

In 1997, Clay Quarterman heard there was another Presbyterian living in Kiev. Roger and Diane McMurrin had begun Music Mission Kiev in 1991. They had also helped start the Church of the Holy Trinity, an interdenominational work with a large ministry to widows, a strong Evangelism Explosion program, and a very developed music program. Roger begged Clay to send a Ukrainian pastor to take over the work. Ivan Bespalov was called from Odessa to Kiev, and the church changed its name to the Presbyterian Church of the Holy Trinity (PCHT).

On April 28, 2002, the church ordained elders and became an official congregation of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Ukraine (EPCU). For 20 years, the church has met in rented facilities at Shevchenko Blvd. #50 – 4th floor, in the National Choir Building (Veryovki).

However, in 2005, the McMurrins formed a separate congregation, St. Paul’s Evangelical Church, taking many of the Holy Trinity congregants with them. Although this was a traumatic event, it was not without some good results. It eventuated in a separate evangelical church; it also caused those who stayed in the Holy Trinity church to clarify their vision as a self-sustaining Presbyterian church.

Currently (2017), there are six men being trained for leadership in Holy Trinity. A number of the young adults have taken on responsibilities in music, publications, and teaching. The praise band is active on its own, serving with other churches and at Christian conferences and concerts.

Jim and Marianna Peipon and their children were an integral part of Holy Trinity church, involving its members in their “Ukraine Medical Outreach” ministry and in various works of mercy and hospital visitation.

PCHT owns a ministry center at Krasnoarmeiska (Red Army) Street 33, apt. 8, near Lva Tolstovo Square, and they share their office with MTW.

This year (2017), Pastor Ivan celebrates his 20th year of faithful service in the church.

Kiev Church Plants

In 2002, an MTW team was formed to plant “Covenant of Grace” Presbyterian Church in the Kharkovsky area on the left bank of Kiev. This was led by seminarian Artyom Bedarev and overseen by Heero Hacquebord. The Bedarev family suffered tragedies when their daughter contracted cancer in 2006. Sadly, Artyom was recruited in September 2006 for a work in Donetsk, and reported to presbytery in October that he “did not feel called as a church planter” and moved to Donetsk. The work was closed shortly thereafter, having no leader to develop the ministry. Members moved to the other Kiev churches.

In 2004, Max Tikhonov began a new church in the Solomensky area of Kiev, focusing on University students and young adults. The Solomensky church grew to become a particular church in October 21, 2014, taking the name “Church of the Big City.” They purchased an office and ministry center near Svyatoshino Metro, where David Pervis also held English Club from 2015-2017. Here, they have held regular movie nights and many other activities. Worship services, however, have been in rented facilities to accommodate the larger size of the group.

This church has a vision for expansion. They attempted to establish a church plant in Obolon, but this was closed by presbytery in 2016. They continue with ongoing discipleship training and very active summer camp programs (such as X-way).

The Big City church sent out a group of its members in 2016 to form a separate church plant in Kiev, called “Liberty”, led by Pastor Max. This group has organized their own separate camp and training programs. They have even started plans for a third church on the left bank of Kiev.

In 2015, Holy Trinity church began an English worship service on Sunday evenings, along with catechism classes, and members of the church began an English club in 2017. Mel and Martha Pike returned to Ukraine in October 2017 to help develop this work into a separate church for internationals.

Kherson

A CoMission team of the PCA also served in Kherson, followed by MTW missionaries Mel and Cindie Pike and Melinda Wallace in 2001. A church was begun, and called Andrei Revtov as pastor. He resigned this pastorate in early 2005 for health reasons, moving to Kiev. The church was supplied for a time by seminarian Sergei Nakul, and the Presbyterian church established a center for ministry to street-children. Sadly, Revtov eventually returned and left the church in scandal. The church called Sergei Kukushkin as pastor, who continues serving there. Jamie and Nadia Thornton of MTW have also assisted in the church’s ministry for over ten years.

Until 2006, the church met in ten locations, including the Oblast Teacher’s Building downtown, near an oak supposedly planted by Pushkin. They then received a grant from an American donor, bought land, and built a church building at âóë. Ñi÷îâèõ ñòðiëüöiâ (Êàëiíiíà), 130.

In January 2013, Mel’s first wife Cindie Pike died tragically in Kherson – a grief and shock to the whole denomination. Her dedication and gifts of perception and discernment have been greatly missed. She even helped compile much of the data used in this present history. Mel moved to the USA for several years, returning in 2017 to work in Kiev, along with his new wife, Martha.

Tsurupinsk Church Plant

The Kherson church started a church plant across the river, in the nearby township of Tsurupinsk. This was led by seminarian Mykola Koretsky, who graduated ERSU in 2010 and went on to study in Kampen, Netherlands, receiving his degree there in 2015. The church’s first worship was on January 7, 2005. Sadly, this work did not grow, and was closed by Presbytery in 2016. Koretsky is presently joining a church plant in Derby, UK.

Cheryomushky (South Odessa)

In 2002, Odessa’s church formed a team of Ukrainians and one American missionary, Jill DeVere, to plant a daughter church in the southern region of Odessa. A mission church was established with Valera Zadorozhny as pastor, and ERSU student Roman Prihodko as his assistant. They began public worship in January 2003. The Cheryomushky church plant met in the Dom Prirodi for over two years, but the work was discontinued in October, 2005, and the members were taken back into the mother church.

Kotovskovo (North Odessa)

The EPCO began another church-plant in 2006 for the Kotovskovo region under the leadership of Pastor George Kadyan, who had been pastor of the Pastera church in downtown Odessa. For several years they rented facilities at Maladaya Gvardia. Then, in 2016, they moved to a house on 12-aya Liniya Street which could serve both as manse and ministry center. They work closely with the MTW team there, holding summer camps each year with teams from the USA. They have an active English outreach ministry developed by Jacoby and Lera Nelson, with help from MTW missionaries Robin Price, Bob and Andrea Burnham, and Randy and Debra Warren.

Kharkov

The first group of Ukrainian Presbyterians to make up a Church Planting Team was sent from the Odessa and Izmail churches in 1999. They went to Kharkov at the invitation of Doctor Vladimir Borisovich Starodub on behalf of a group of believers interested in the Reformed faith. Members of the team included George Kadyan, Sergei and Marina Orzhenski, Peter Kolmikov, Oksana Ponomarenko, Katya Tovchigrechka and Snizhana Popova.

Dedication of Odessa Team for church planting in Kharkov, 1999

Dr. Vladimir Borisovich became pastor and has continued to oversee the growing church, being assisted by gifted teacher and ERSU student Sergei Sudakov.

Ordination of elders Sergei Sudakov and Yuri Boiko, 2014

The Kharkov church was particularized when elders were ordained there on Nov 23, 2014. The church has worked closely with university workers of CCX (Intervarsity Fellowship), including the Kharkov director Vassili Agarkov.

The church sent church member Anna Sterlieva to work with CCX in Shevchenko University in Kiev, where she is also active in Holy Trinity church. The Kharkov church also sent church member Alexander Buichkov to Oleksandriya in 2015 as a self-supporting church planter under their oversight.

Karlovka (Poltava Region)

Karlovka is a town of 20,000 people, and an independent, former charismatic church there became interested in joining the EPCU in 2009. Pastor Vladimir Shestun had been studying the Reformed faith and attended UBS seminary. He was examined and joined the EPCU and led the church in a process to join the denomination, with visits from various members of presbytery.

As a self-supporting work, the church purchased a house and remodeled it as a church building. The church has around 70 people in active attendance, with several men active in leadership.

Lviv

In 2006, missionaries and Ukrainian Presbyterians in Odessa and Nikolaev felt the need to form a Ukrainian-speaking ministry in western Ukraine. A cross-cultural team was formed of Americans, Ukrainians, and South Africans, all of whom had to study Ukrainian language. They began their work in university ministry, art and music, English ministry, and mercy ministry, building relationships and planting the Holy Trinity Presbyterian Church (http://www.lvivtserkva.com/).

Worship was begun in 2012 with worship style and liturgy adapted to the context.

Heero Hacquebord is pastor of the church, which has purchased land for development of its own building.

Seeing the great need for Reformed materials in the Ukrainian language, they formed Kraynebo Publishing, and have translated and published a number of works, including a professional music series for teaching catechism to children.

Doug Shepherd transferred his experience in the “Odessa Project” into a new program of ongoing mentoring and training. Using the Lion theme of Lviv, they have organized the “Levchiki” program for kids, “Leopolis Green” summer English programs, mentoring programs, youth programs, and an active university outreach.

Their vision is to expand the work into other areas in western Ukraine.

Oleksandriya (Kirovohrad Region)

ERSU seminary student Sasha Buichkov was a member of Kharkov church and needed to move to Oleksandriya in central Ukraine in 2015. He asked the elders to send him there as a self-supporting church planter, under their oversight. He has worked there with some occasional assistance, not only from Kharkov, but from other churches of the EPCU, offering English classes, movie nights, children’s clubs, etc. They began Sabbath worship in 2016.

Preparing Ukrainian Leaders

As the first churches were being established, the need for leadership training was immediately apparent. Clay Quarterman had experience as a professor in the Portuguese Bible Institute (Tojal, Portugal), and he was already holding discipleship meetings with Ivan Bespalov and Sasha Korsakov when Dal Stanton arrived in August 1995. Dal and Clay planned in September 1995 for a “ramp” to move contacts from the informal CoMission Bible studies to a church and worship format.

They started planned a School of Church Planting (SCP), which quickly became the “School of Theology and Church Expansion” (STCE). The STCE and the “ramp” were to move people from the educational program into the church program, teaching leaders what the church and its leadership were all about.

It should be noted that it takes many years to develop native Russian- and Ukrainian-speaking pastors and professors, so a number of interpreters have been an integral part of the life and work of churches and seminary. They have developed an accurate theological vocabulary, helped in the meeting of minds, and have been the voice of foreign visitors. The churches owe a debt of gratitude to the following seminary interpreters and translators, among many others: Natasha Shevtsova, Larissa, Bogdan (from Cherkassy), Sergei Nakul, Snizhana Popova, Vladislav and Lena Makarov, Ildar Gazizulin, and Helen Bogat (wife of ERSU administrator Alexander, and head interpreter for many years). Dima Bintsarovsky has also headed the seminary translation team for years.

Other interpreters have helped immensely in various ways in the churches: Sasha and Olya Korsakov, Ivan Bespalov, Leonid Kolker, Anya (Baklanova) Dudkina, Sashko Nezamutdinov, Lyuda Betina, Olga Kornilyuk, and Anya Plachkova, among many others.

Many of these interpreters have themselves been deepened in their knowledge of Christ and in church leadership as they have passed on these messages to others. We are thankful for their service to Christ and to us.

Training “The Force”

As early as 1994, the MTW Team identified a group of emerging leaders variously called “The Ministry Group”, “The Ministry Team”, “The Force Multipliers”, or “The Force”. These could be trained in English, allowing the missionaries immediately to provide deeper training for some of the rising leaders.

The “School of Theology and Church Expansion” (STCE) began in November 1994, meeting on Monday nights in the missionary school facility at Novoselskogo Street #97 (4th floor), with half a dozen students. Those in regular attendance in Odessa: Olya, Sasha and Sergei Korsakov, Ivan and Lucia Bespalov, and Dima Ivanov. Clay also traveled to Belgorod to present the same materials to six students in the emerging church there, including Sergei and Lyuda Betin, Victor Lukoshkin, and Lyuda Shamota.

This local leadership training was supplemented by visiting professors and later by lectures in Kiev at Ukraine Biblical Seminary (UBS), which began in July 1996.

Proto-Presbytery

In order to teach the Biblical principle of joint rule (Presbyterian leadership), the missionaries invited developing leaders in each emerging church to meet as a group of “Proto-elders” or a “Proto-session” to assist the church planting pastor in making local decisions. Ecclesiastical rules required a local church planter (in this case, the ordained missionary) to continue in authority until local leaders could be developed, elected, and ordained. Yet, in this way, he could share these decisions with other developing leaders. This provided training for the emerging leaders, and it allowed the churches to participate in self-determination long before their official “particularization” (organization).

The Presbyterian principle of connectivity among the churches was also taught by holding “Proto-Presbytery” meetings twice a year, beginning in April 1998. Proto-elders from each emerging church were brought together with all the ordained missionaries and pastors to deliberate on common action of the churches and to begin the infrastructures that would eventually become the autonomous Presbytery of Ukraine.

“Odessa Project” Mentoring Project

In 1996, former CoMission member Louisa McCullough organized the first in a series of American Short Term Teams to assist the Church Planting Team. That summer, Dal Stanton and Doug Shepherd organized the first “Odessa Project”. Odessa Project was designed to team up American and Ukrainian college-age adults in a challenging, cross-cultural, study and ministry experience, training young leaders in Ukraine, while at the same time giving Americans a life-changing vision for the worldwide work of missions outreach. This discipleship and mentoring program became an effective model for later development in Lviv and beyond.

Odessa Presbyterian Seminary

There were enough emerging leaders by 1997 that the need for a full seminary curriculum was evident, so Clay Quarterman organized the Odessa Presbyterian Seminary (OPS). With the help of Eric Huber, a protocol was established with Chesapeake Seminary (Baltimore, MD) for use of their materials, some of which were translated by Sodeistviye. The first class was started with five men in September 1997.

Classes were often recorded in the classes at Chicherina #60 (later renamed Uspenska St.) so that others could study at-a-distance. Immediately, tapes were sent to Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, where the first OPS extension center had 3 students. Clay traveled to visit them once a month. When Pastors George Kadyan and Ivan Bespalov moved to Kiev on mission work, they were able to continue their studies in this way. Tapes were sent to students in Izmail, Belgorod-Dnestrovsky, Nikolaev, and Kiev. OPS was later merged into the ERSU seminary.

Odessa Presbyterian Students in Kiev for seminary classes

Evangelical Reformed Seminary of Ukraine (ERSU)

In March, 1997, Clay was introduced to Marten Nap, a missionary in Kiev from the Reformed Church of the Netherlands (liberated). Marten had a seminary in his flat (#13 Lva Tolstogo, across the street from Shevchenko State University). The Dutch mission was working with churches of the Ukrainian Evangelical Reformed Church (UERC), and Marten was training three of their students in his kitchen. It was affectionately known as the “Kitchen Seminary”.

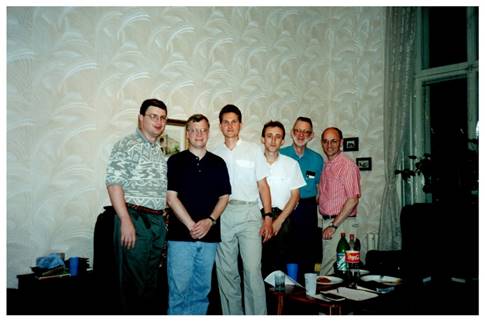

First meeting of Marten Nap and Clay Quarterman, with McMurrins 1997

Common interests led Clay and Marten to seek other Reformed workers to form an ongoing Ukrainian institution. They organized the “Conference of Reformed and Presbyterian Churches Working in Ukraine” on November 6 and 7, 1998. Participants came from Reformed bodies in Holland, America, Canada, Hungary, and Ukraine, with representatives from the following churches and missions:

The Ukrainian Evangelical Reformed Churches (UERC), the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Ukraine (EPCU), and the Reformed Church of the Sub Carpathians (KRE), as well as foreign sponsors: the Reformed Churches Liberated in Gelderland and Flevoland, Mission to the World of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA), and the United Reformed Churches in North America (URCNA).

Out of this came a Joint Seminary Task Force which prepared a “Proposal for a United Reformed and Presbyterian Seminary in Ukraine” that was approved by the Conference in September, 1999, taking the name Evangelical Reformed Seminary of Ukraine (ERSU).

The plan was approved by the presbytery of the EPCU and by the classis of the UERC in November, 1999. Official registration was granted ERSU in February 2003. A joint Board was appointed by the UERC and EPCU, providing the infrastructure for the new seminary. Chairman of the Board was Jan Werkman of the Dutch mission in Kiev, followed by Cor Harryvan of the same mission (2005-2017), whose faithful service and support was inestimable.

In order to register a legal seminary, the UERC and the EPCU had to form a legal union of churches (Soyuz) under Ukrainian law, which was called the Union of Evangelical Reformed Churches of Ukraine (UERCU), and was recognized by the government in October, 2001. The UERC Synod and EPCU Presbytery continue to function independently, and hold joint meetings of the legal union (“Sobor”) yearly. Their first “Round Table” meeting was in June, 2002, when Valera Babuinin was elected Secretary. Seminary Board members are elected jointly by the UERC and EPCU.

ERSU Seminary Staff

The first Senior Staff consisted of Clay Quarterman (President), Marten Nap (Academic Dean), and Eric Huber (Dean of Students, MTW). In 2001, Jos Colijn joined ERSU from Hattem mission, replacing Marten Nap as Academic Dean. Rod Gorter (CRC serving with ITEM) served as Dean of Students from 2004. The staff jokingly referred to themselves as the “Rod and Staff” of the seminary.

Scott Andes (World Witness/ARP) replaced Rod as Dean of Students when Scott moved to Ukraine in 2007, and he served until 2016. In 2013, Jos Colijn went to Kampen University, and Erik van Alten took his place as Academic Dean; two years later, Erik replaced Clay Quarterman as President. Alister Torrens (serving with ITEM) joined the staff in 2014 and then replaced Erik as Academic Dean.

ERSU offers the M.Div. degree, and has had several students accepted for further graduate work at Kampen University in the Netherlands. The plan is to prepare and continually add more Ukrainians to the staff and to the resident faculty.

Pastor Andrei Dilyuk of Minsk, graduate of ERSU in 2007, became professor of biblical languages at ERSU. ERSU graduate Dima Bintsarovsky did an amazing job as ERSU webmaster and editor, even while finishing degrees with honors at both ERSU and Kampen. He was then invited onto the Staff of ERSU, where his contributions are varied and inestimable.

ERSU administrators have been Alexander Bogat, Dinis Lukoshkin, and Dima Zaitsev (2017-present). Anya Baklanova (later Dudkina) served as administrative assistant in Odessa and Registrar until 2007, being followed as Registrar by Helena Bintsarovskaya.

Librarians have been Masha Kalmuikova, Sodik Kuvondikov, and Dmitro Khomoretsky, who organized, catalogued, and maintained the ERSU theological library. In 2003, ERSU received a generous grant for the library from the Fesenko Fund in Canada, boosting its holdings, and MTW missionary Susan Wood came from Portugal to train our librarians. ERSU now has over 5000 volumes in their holdings.

ERSU Class Sessions

The first classes of ERSU were held in May 2000 in the Nap’s flat at Lva Tolstogo 13, across the street from Shevchenko State University, and the first class had 20 students. Subsequent sessions were held in area sanatoriums: Prolisok (Kozyn), Zmena (Klavdievo), Zhuravushka, Pusha-voditsya, etc. A second class of 17 students was added in September 2002, when the first Convocation was held. ERSU’s highest enrollment was 55 students.

The seminary continued several years to maintain offices and research libraries both in Kiev and Odessa, where monthly tutorials were held with the students. After years of renting office space in central Kiev (Gorkovo St. 21 and Darwin St. 5), the seminary purchased an office in 2006 at Polupanova St. 10, Kiev, to house its study center, offices, and library.

Since Fall 2014, ERSU has been seeking a unified campus to house our students while they study. In these three years, the Staff has actively worked to locate and design three options, each of which fell through. Yet, the search continues.

Educational Programs

The main goal of ERSU is the training of pastors in its MDiv program. But ERSU also serves other needs of the churches. Other levels of education are needed in the church for journalists, women, and lay leaders. ERSU has had several women in its Masters program, and has encouraged women’s work, helping organize the Lydia Women’s Institute in Kiev and Odessa.

Seeing a great need in middle-level education, ERSU organized the “Istoki” Bible College program in 2006, which ran until 2009 under the oversight of Alexander Bukovetsky. Three students completed their 2-year certificate and two of these went on into the Masters program of ERSU.

In 2012, ERSU launched the Online Bible College to help fill this need, providing several courses by extension, using materials from Third Millennium Ministries (IIIrd Mil). ERSU also offered some Masters-level courses by extension (Distance Learning Program) beginning in 2010.

Seeing many needs for better Christian Education (CE) among our churches, ERSU organized a ministry of CE in 2015, developing literature, providing seminars and training, creating a CE library and a CE website (www.ProSvita.ersu.org) to provide resources for training in the local churches.

At date of writing (2017), there have been 24 students to graduate from ERSU with MDiv degrees, three with Bachelor degrees, and three who completed the “Istoki” Bible College program. Current enrollment is 24 MDiv students and 20 students enrolled in the Online Bible College.

In 2015, when ERSU had a special celebration of its 15th anniversary, with international visitors, Dr. Quarterman stepped down as president, passing the school bell to Erik Van Alten as the seminary’s second president.

The Ukraine Partnership

Individual churches of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA), having prayed for decades that God would open doors for the Gospel into the USSR, began connecting on their own with individual churches and believers in Ukraine. A group of these churches banded together with MTW, the mission arm of the PCA, into a “Ukraine Partnership”, to coordinate these efforts and commit the needed funds.

They helped believers from various evangelical churches in Ukraine to start small businesses, hold evangelism and training projects, build buildings, etc. One group of pastors calling themselves the “Brotherhood” met in Rovno with Clay Quarterman and Richard Hostetter of the Partnership. One common need of all these works was theological training for national pastors, so the Ukraine Partnership agreed to form a seminary called UBS. The pastors of the Brotherhood and other evangelical churches were invited to train, along with our own students from Odessa Presbyterian Seminary.

Ukraine Biblical Seminary (UBS)

Richard Watson, former Dean of Reformed Theological Seminary (RTS) in Jackson, Mississippi, was chosen to organize the work, inviting Reformed professors from RTS, Westminster, and Covenant Seminaries to teach in intensive one-week sessions. Tanya Becker handled the administration in Ukraine. Classes began in Kiev in July 1996, continuing for 20 years.

For the first four years, Clay Quarterman and Rod Gorter took the students of Odessa Presbyterian Seminary regularly to these intensive training sessions. The sessions were supplemented with local mentoring by MTW missionaries and with additional classes of Odessa Presbyterian Seminary. In 1997, when the Joint Seminary Project sought to unite all Reformed works in Ukraine for training leaders, UBS chose to continue its work independently, and subsequent Presbyterian and Reformed students were trained in ERSU.

RITE Seminary (Donetsk)

There was a CoMission team in Donetsk in the 1990s, but it was sponsored by churches not connected to MTW. MTW’s CoMission work was limited to three southern regions of Ukraine (Odessa, Nikolaev, and Kherson), and their work was focused there. Yet, Reformed and Presbyterian pastors from the West began traveling to Donetsk and had connected initially with the evangelistic work of the Baptist church in Makeyevka.

Rev. Nick Vogelzang of Denver, Colorado, organized Donetsk Seminary in 1991 at the request of Dr. Joel Nederhood of “The Back to God Hour” radio broadcast.

Beginning in 1995, ITEM (International Theological Education Ministries, formerly Christ for Russia) sent Reformed pastors and professors to teach in the Baptist church’s Donetsk Regional Bible School. A new building was built in Makeyevka. It was registered as the Donetsk Regional Theological College. It began full time classes in the fall of 1998.

Pastor Rod Gorter of the Christian Reformed Church, one of the teachers who traveled to teach in Donetsk, moved to Odessa in 1998 as an ITEM missionary with the MTW Team, serving also on the Staff of ERSU Seminary. Rod continued teaching in the Donetsk Bible school, and two graduates moved to Odessa and trained in ERSU seminary.

Clay Quarterman and Rod attended the Donetsk Pastors’ Conference in May 2003. However, ITEM discontinued its relationship with the Bible school at that time, and a group led by Merle Messer organized a mission to continue training 20 of the students. It was called RITE (Reformed International Theological Education), and Natasha Silesnova was administrator. Some of the students eventually formed an independent Reformed church in Donetsk (“The Light of Resurrection”).

When Russian-backed troops invaded the Donbas in 2014, most students fled Donetsk. This unfortunate turn of events had a positive result, however. The school continued its work at Prolisok Sanitorium in Kiev, bringing the administrators and visiting professors in contact with the EPCU pastors and churches and the MTW missionaries, who have enjoyed close fellowship.

Translation & Publishing

The Odessa Team was involved in translation and publishing as early as 1994 through their “Sodeistviye” humanitarian aid organization. The Team first contracted the republication of The Westminster Confession of Faith in Ukrainian for churches in western Ukraine (1995). Lack of Reformed materials then led to the translation of The Book of Church Order and Sunday school materials based on the Westminster Catechism. As the translation staff grew in ability, 25 books were translated into Russian or Ukrainian. A basic reformed theology was made available in R. C. Sproul’s Essential Truths of the Christian Faith, and a broad range of materials have enriched the Evangelical repertoire, including hymnology, additional theological works, and women’s ministry.

In December 2004, the Team closed the publishing arm of Sodeistviye so that the Presbytery could form its own publishing house – TULIP Publishing, with headquarters in the downtown Odessa church (http://www.tulip.org.ua). Ludmilla Voronchenko has done a great job as Director, promoting and distributing Reformed works across Ukraine and Russia, and developing relationships with other publishing houses.

Since TULIP in Odessa publishes most of its material for the Russian-speaking community, the Presbyterians in Lviv organized Kraynebo Publishing (http://www.kraynebo.com), producing Ukrainian literature and resources.

In 2015, the leadership of the Evangelical Reformed Seminary of Ukraine (ERSU) began an online theological Journal, “Reformed Viewpoint” (http://journal.ersu.org/), attempting to produce materials for this region at a high academic level similar to Western theological journals. ERSU also maintains an online repository of Reformed materials at http://www.reformed.org.ua/ , as well as their seminary website http://www.seminary.ersu.org/ , Christian education site http://www.prosvita.ersu.org/ , and online Bible college website http://www.college.ersu.org/. In 2017, ERSU cooperated in the production of a commemorative volume for the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation.

Reformed Worldview and Culture

The Presbyterians and Reformed churches have always emphasized that all of life is to be lived to the glory of God, Soli Deo Gloria. As John Calvin wrote, all of life is worship. Thus, our daily work, the arts, and all of culture is to be lived unto God’s glory.

This principle of the Reformation has even had a large economic impact on societies where the Reformed churches have gone, as sociologist Max Weber noted in his analysis.

The church in Odessa promoted morals and good business practices by holding numerous seminars and inviting guest speakers. But in 2008, they also organized the Center for Ukrainian Business Projects, which for several years held seminars and developed active relationships with Christian businessmen through the Salty Oak center in Birmingham, Alabama.

Another area of influence has been music and the arts. The choir of Tenth Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the Westminster Brass visited the Odessa church and even performed in City Park July 2008.

Through the years, “Sodeistviye” helped the Presbyterian churches organize many organ concerts and cultural events in connection with the church and other agencies, such as the International Christmas Festivals held yearly in the Pastera church beginning in 2004, joining with the Bavaria House, local and international singers and musicians, to provide free concerts for the community. Festivals have also been held at Easter and throughout the year, in addition to monthly organ concerts and musical ensembles sponsored by its “Fund of the Christian Art Revival”.

Social Work

Christian churches have always followed Jesus’ pattern of caring for the poor and ministering to the physical, spiritual, and emotional needs of people both inside and outside the church. But beside the care shown by each of the churches of the EPCU, there have been specific ministries developed to focus on specific needs.

“Sodeistviye” Fund

“Sodeistviye” Odessa Regional Charity Fund was established in the early 1990s – one of the first things organized by the missionaries. They registered as a Humanitarian Aid organization in order to receive containers of aid and distribute them to organizations in need – a common situation in the 1990s, when many social structures were broken. They first received 24 boxes of Humanitarian Aid at the airport in Aug 1995. In summer 1996, the first humanitarian aid container arrived by ship. They developed relationships with orphanages, hospitals, and clinics in the region in order to know their needs and oversee their use of the aid. They eventually became officially registered as a Humanitarian Aid organization, able to import and distribute aid free of charge.

Members of the churches cooperated in the distribution, which even included refurbishing hospital rooms and providing laparoscopic equipment to the Odessa Regional hospital.

Laura Batushkovo was a faithful worker in this work for over a decade, as well as coordinating work for MTW and the Odessa Family Counseling Center, assisted by Tanya Savchuk, another church member who was always able to “get things done”.

“Dzherelo” (Belgorod-Dnestrovsky)

A similar Humanitarian Aid organization was established in 1997 in Belgorod-Dnestrovsky -- “Dzherelo”, which continues to serve the Belgorod Christian Clinic, orphanages, and other organizations. Victor and Svyeta Lukoshkin of the Presbyterian church have handled the lion’s share of administration of the organization.

Belgorod-Dnestrovsky Clinic

In 1997 a medical clinic was started in Belgorod-Dnestrovsky under the leadership of Dr. Sergei Betin, who also serves as pastor. Missionary nurse Adeline Wallace served there tirelessly from 2000-2011. Visiting American doctors and nurses found many ways to meet physical and spiritual needs there. An association of church people was formed to oversee the project, and funds were found for purchase and reconstruction of a three-story clinic, staffed by Ukrainian Christian doctors. American Medical Teams visit several times each year, working with people from the church and clinic. More local doctors have been added with time, with specializations in dentistry, gynecology, pharmacy, and even a children’s wing. The clinic has become widely known in the community for their quality care and generous hearts.

“Rodnik” Family Counseling Center of Odessa

The "Rodnik" Family Life Counseling Center is a ministry of members of the Evangelical Reformed Presbyterian Church of Odessa, with participation of other Christian counselors. They promote Christian ethics and life skills in Odessa families, as well as outreach to orphans and needy families in the community.

It began with seminars by Dr. Langston Haygood of Birmingham, Alabama. Its first director was Erika Shteker, beginning work in March 2008. Lena Kolker followed as director until 2017, when Sergei Betin took the leadership.

Its offices are now in the Odessa Presbyterian church building, using counselors from other evangelical churches. They have also been busy providing counsel and humanitarian aid to refugees from the war in eastern Ukraine.

“Genesis house” in Kiev

In addition to church members’ visits to orphanages, PCHT has helped develop the Genesis House. A British sponsor on visiting Ukraine sought to help orphans by organizing a private orphanage. As this was not allowed by the government, a home was purchased where a sponsor family from Holy Trinity Presbyterian Church would live and provide foster care for the children in a family setting. The first was the Oleksandr Donskyi family, which lived there until 2015, followed by the Oleg Vovk family. This ministry has had an eternal impact in the lives of these children, who have also been actively involved in the Holy Trinity church’s Sunday school and church life.

Life Care Center (Izmail)